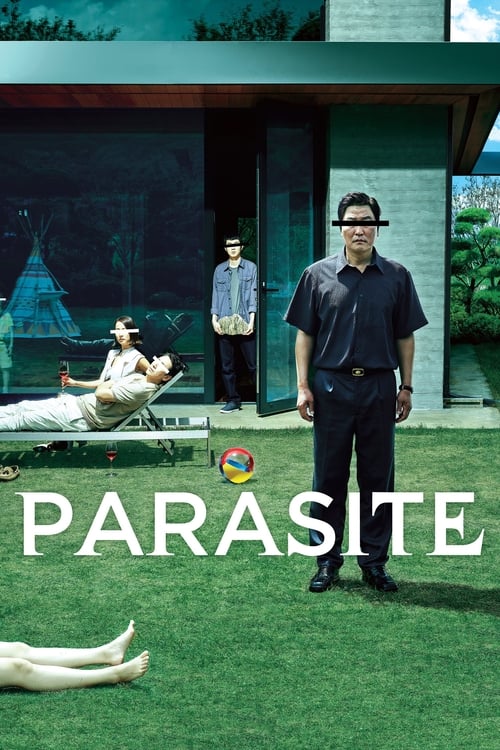

The Godfather

Spanning the years 1945 to 1955, a chronicle of the fictional Italian-American Corleone crime family. When organized crime family patriarch, Vito Corleone barely survives an attempt on his life, his youngest son, Michael steps in to take care of the would-be killers, launching a campaign of bloody revenge.

EPISODENEW.COM Review

To speak of Francis Ford Coppola’s 1972 epic, The Godfather, as merely a “crime drama” is to diminish a masterwork of American cinema. This isn’t a film about gangsters; it’s a profound, chilling meditation on power, family, and the corrupting nature of the American Dream itself, meticulously sculpted over a decade of fictionalized history.

Coppola’s direction is a ballet of controlled intensity. He doesn't just show us violence; he makes us feel its insidious creep. Consider the opening scene, Bonasera’s plea, bathed in the sepia tones of cinematographer Gordon Willis. The darkness isn't just aesthetic; it’s a visual metaphor for the moral murkiness that defines the Corleone world, a world where justice is bought, not earned. The famous “Godfather lighting” – faces half-obscured, eyes often in shadow – doesn't merely create atmosphere; it speaks to the hidden motives, the unspoken threats, the internal conflicts simmering beneath stoic exteriors.

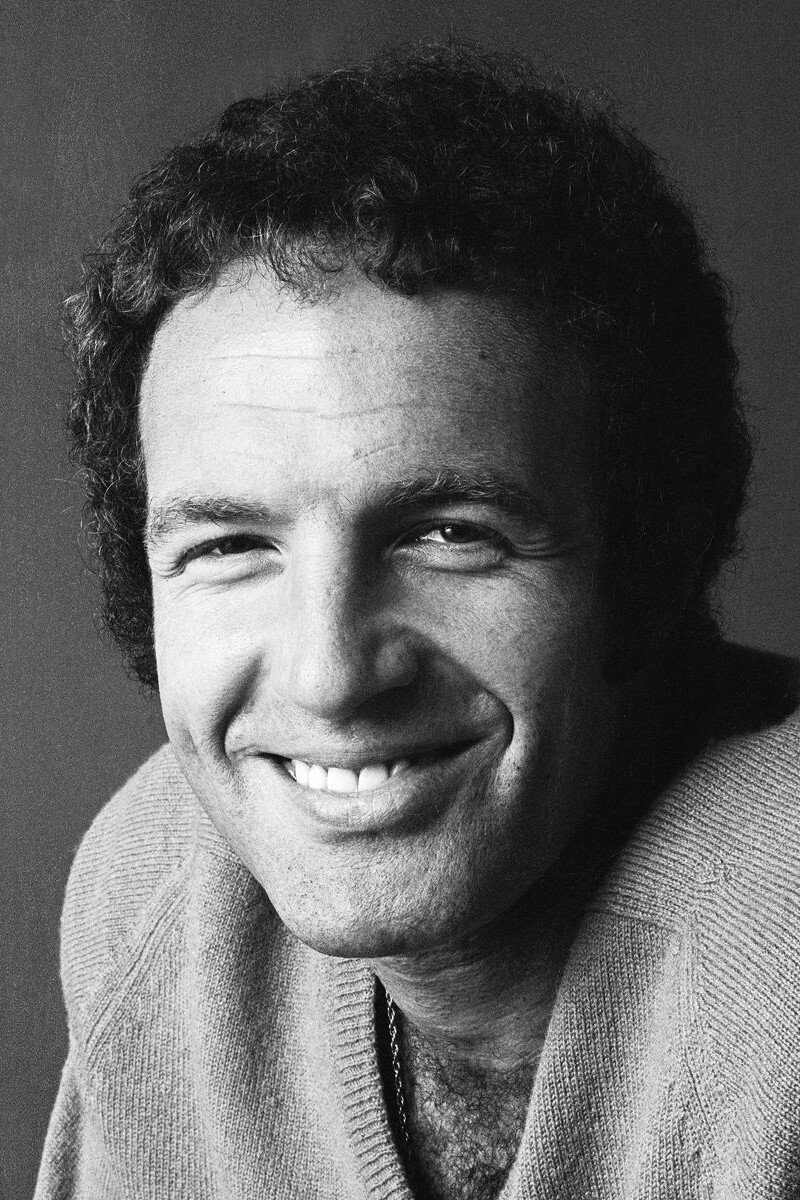

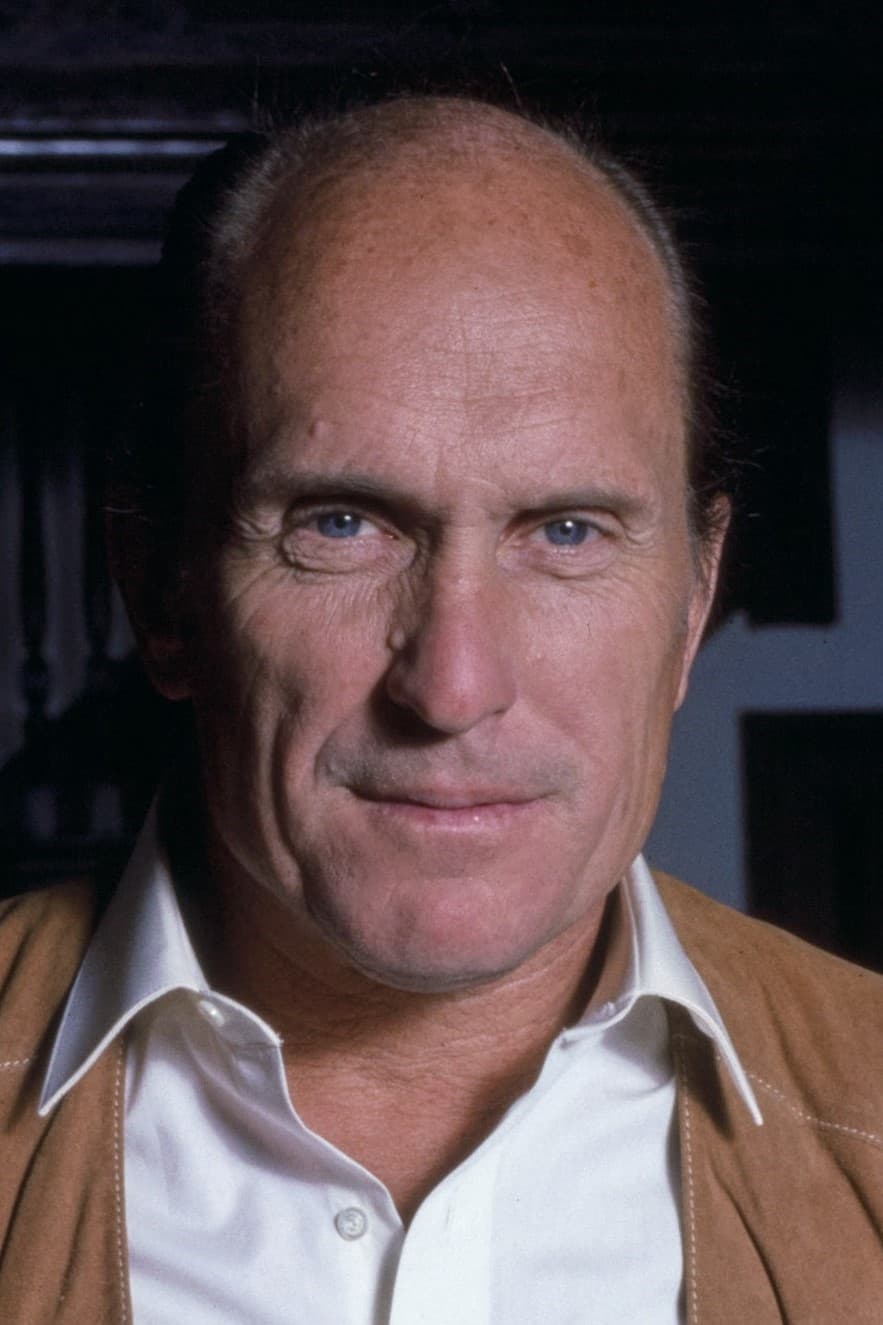

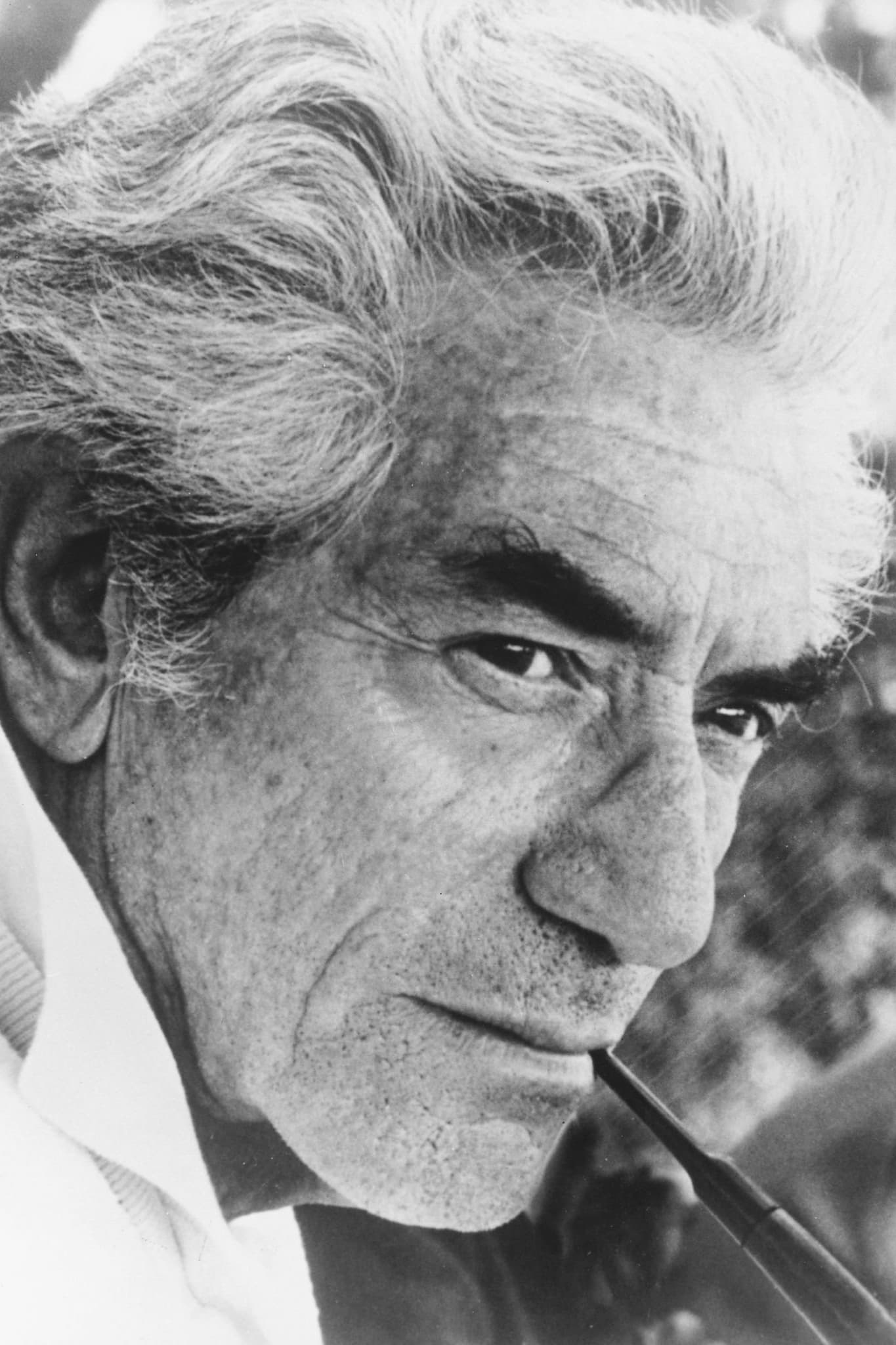

The screenplay, co-written by Coppola and Mario Puzo, is a tapestry of consequence. It’s in the quiet moments, the subtle shifts in dialogue, that the true genius lies. Michael Corleone’s transformation, portrayed with terrifying precision by Al Pacino, is not a sudden leap but a gradual, almost imperceptible descent. From the outsider at Connie’s wedding, dismissive of his family’s business, to the ruthless patriarch ordering a massacre during a baptism, Pacino’s performance is a masterclass in controlled implosion. Brando’s Vito, of course, is iconic, his gravelly voice and almost theatrical slowness embodying a dying era of brutal pragmatism. Yet, it’s the nuanced performances of James Caan’s volatile Sonny and Robert Duvall’s stoic Tom Hagen that often go underappreciated, each a vital cog in the family’s intricate machinery.

Is the film without fault? Perhaps its expansive nature occasionally tests the patience of a modern audience accustomed to quicker pacing. And while the female characters, particularly Diane Keaton’s Kay, serve as crucial moral compasses or tragic observers, they are undeniably peripheral to the patriarchal power struggle. Yet, these are minor quibbles in a film that fundamentally reshaped how we perceive narrative, character, and the very concept of cinematic epic. The Godfather isn't just a film; it’s a cultural touchstone, a ruthless examination of inherited legacy and the cost of absolute power that continues to resonate with uncomfortable truths. It demands to be studied, not merely watched.